The RKO film King Kong dramatized the true story of Carl Denham and his misadventure with the mysterious beast from “Skull Island” — a movie that eventually, one could argue, overwhelmed the event it loosely depicted.

One of the very few pieces of material evidence in existence that illustrates Denham communicating in any way whatsoever with King Kong producer Merian C. Cooper comes in the form of correspondence during Denham’s incarceration at New York’s imaginatively named City Prison (more colorfully known as The Tombs).

We can see in hindsight that Denham’s eventual deal with RKO — an agreement necessitated by the astounding fiscal damage created by the giant beast — was, at first, primarily a deal with Cooper, who at that point was still technically an independent producer. For Denham to collect in full, RKO president David O. Selznick would have to buy into the film on behalf of the studio—and it was a hard sell from the very beginning.

This one-page missive is the only correspondence left in existence regarding the deal that gave RKO rights to the Kong story — and, it should be noted, the letter is dated well after Cooper began production of King Kong. Cooper was never one to wait for permission. In fact, on December 18th, 1931 — the very evening that the beast wrecked havoc on New York — Cooper sent a memo to Selznick urging the cessation of production on Creation. "I suggest a prehistoric Giant Gorilla..."

With that said, how Cooper and RKO became fascinated with huge beasts is a fairly fascinating tale in itself, which will eventually involve giant lizards.

The Adventurer

Merian Coldwell Cooper was nothing if not a risk-taker. “A straightforward man of action, Cooper had prodigious energy and youthful enthusiasm,” writes film historian Rudy Behlmer in his introduction to the published register of Merian C. Cooper’s papers (as archived at Brigham Young University). The article is entitled “The Adventures of Merian C. Cooper,” which accurately summarizes his eventful career. Not yet forty years old when he began work at RKO, Cooper had already packed a catalog of exploits into his life. Like Denham, he’d flown in World War I, but was shot down, badly wounded, and held as a prisoner of war until the armistice.1

In 1919 he was game for more; strongly against the spread of Russian communism in Europe, he joined the Polish army and formed the Kosciusko Flying Squadron with Major Cedric E. Fauntleroy to help the Poles resist Bolshevik invasion. In 1920 he was again shot down and captured, this time detained for ten months in a prison camp near Moscow. Along with a Polish officer and an enlisted man, Cooper managed to escape and reach the Latvian border twenty-six days later.

After returning to the U.S. in 1921, Cooper worked as a reporter and feature writer in Minneapolis2 and then in New York at the New York Times, where he wrote autobiographical pieces bylined “A Fortunate Soldier.” He became interested in exploration and joined an around-the-world exploratory cruise as second officer, writing articles for a magazine called Asia. When the expedition photographer quit after a typhoon spooked him, Cooper cabled Ernest Schoedsack, a like-minded newsreel cameraman he’d crossed paths with in Europe. They began shooting extracurricular footage for their own planned film; unfortunately, the schooner burned and, with it, much of the negative.

Undeterred — this is a trait Cooper and Denham shared — Cooper secured funding enabling he and Schoedsack to travel to Turkey and Kurdistan, where they filmed the incredible Grass, an epic record of the annual Bakhtiari tribe migration.

Schoedsack was dismayed to learn that the funding was conditional on participation of world traveler/journalist/spy Marguerite Harrison — whose various exploits deserve far more attention than they’ve received up to now — as he feared for her safety on the journey. (Many believe the “Jack Driscoll” character’s initial derisive attitude toward “Ann Darrow” aboard his ship is a manifestation of Schoedsack’s outlook.)

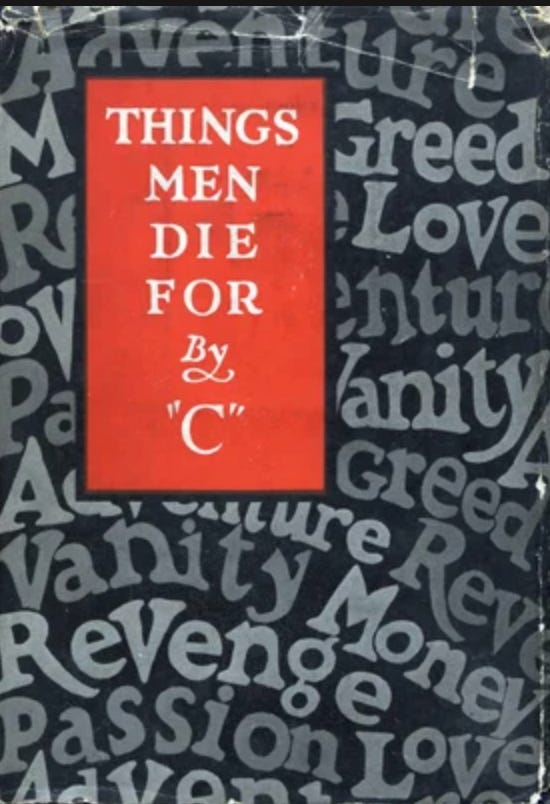

Harrison was, however, a close friend of Cooper; in one of his newspaper pieces, he described how she’d saved his life when he was a prisoner in Russia by smuggling him food. These columns were compiled and published in 1927 as a book entitled Things Men Die For, by “C” (Cooper).3

Cooper took the film out on a lucrative lecture tour where it got the attention of Paramount head Jesse Lasky, who offered to release it. The movie was a sensation, and the Cooper-Schoedsack team followed up in 1927 with Chang, a dramatization of domestic life in the Laotian jungle.

Cooper knew how to put on a show. Chang opened in April of 1927 at New York’s Criterion Theater with a special musical score by Hugo Reisenfeld, the theater’s musical director. Twenty men behind the screen pounded six foot native tomtoms during the climactic elephant stampede, and Paramount's new Magnascope process opened the screen to about twice its normal size for the melee.

You can bet Carl Denham attended.

The Boss

Then came a more traditional narrative film, The Four Feathers, wherein shot-on-location footage from Africa was combined with Hollywood sets, and Fay Wray, the female lead, filmed in those safe confines. Paramount frustrated Cooper, however, by refusing to let him make The Four Feathers as a sound picture, the technology for which was coming into its own at the time. When the film was finished he traveled New York to concentrate on new business interests, while Schoedsack journeyed to Sumatra to film a feature called Rango on his own.

The situation was further darkened when, in response to tepid test screenings, David O. Selznick (who was then assistant to the head of production, B. P. Schulberg, and associate producer for The Four Feathers) felt further finessing was needed and suggested that Paramount staff director Lothar Mendes shoot retakes and additional scenes in the absence of Cooper and Schoedsack. The end result horrified Cooper, as reported in David O’Selznick’s Hollywood:

“Selznick, or Schulberg, had injected…some of the most sickeningly over-grandiloquent titles I had ever seen. I went to the laboratory, and without consulting anyone, quietly cut out of the negative of the finished picture the worst of these god-awful titles and let the picture ride.”

Cooper made up his mind as he exited the Broadway premiere at the Criterion Theater that he would never make another picture unless he was the boss.

That’s when giant lizards enter the story, as you’ll see in Part II …

It was during this period of Cooper’s status as prisoner-of-war that the mysterious — and unrelated — “Captain Cooper” shot motion picture footage of Denham’s 94th Squadron in France.

A roommate during this period was Delos Lovelace, who Cooper would later hire to write the King Kong novelization.

According to the late writer Ron Haver in an article for American Cinematographer magazine, when Harrison learned that the newspaper pieces would appear in book form, she warned him that the book's distribution would endanger her life as she was engaged in “undercover work for the anti-Bolshevik allies.” Cooper quickly (and gallantly) bought up all unsold copies of his book.

A great read! And nice to finally see what a copy of "Things Men Die For" looks like!