Scavengers

From the upcoming book, EIGHTH WONDER: CARL DENHAM AND THE BEAST-GOD OF SKULL ISLAND

Behind a warehouse in a seedier section of Burbank, Alvin Tolliver (not his real name) raised the collar of his jacket and lit his third cigarette. It was dark and getting colder by the minute; he knew it was too much to expect a little respect or courtesy in addition to prompt payment, but being kept waiting on a consistent basis still raised his ire. A guy could get mugged in a place like this.

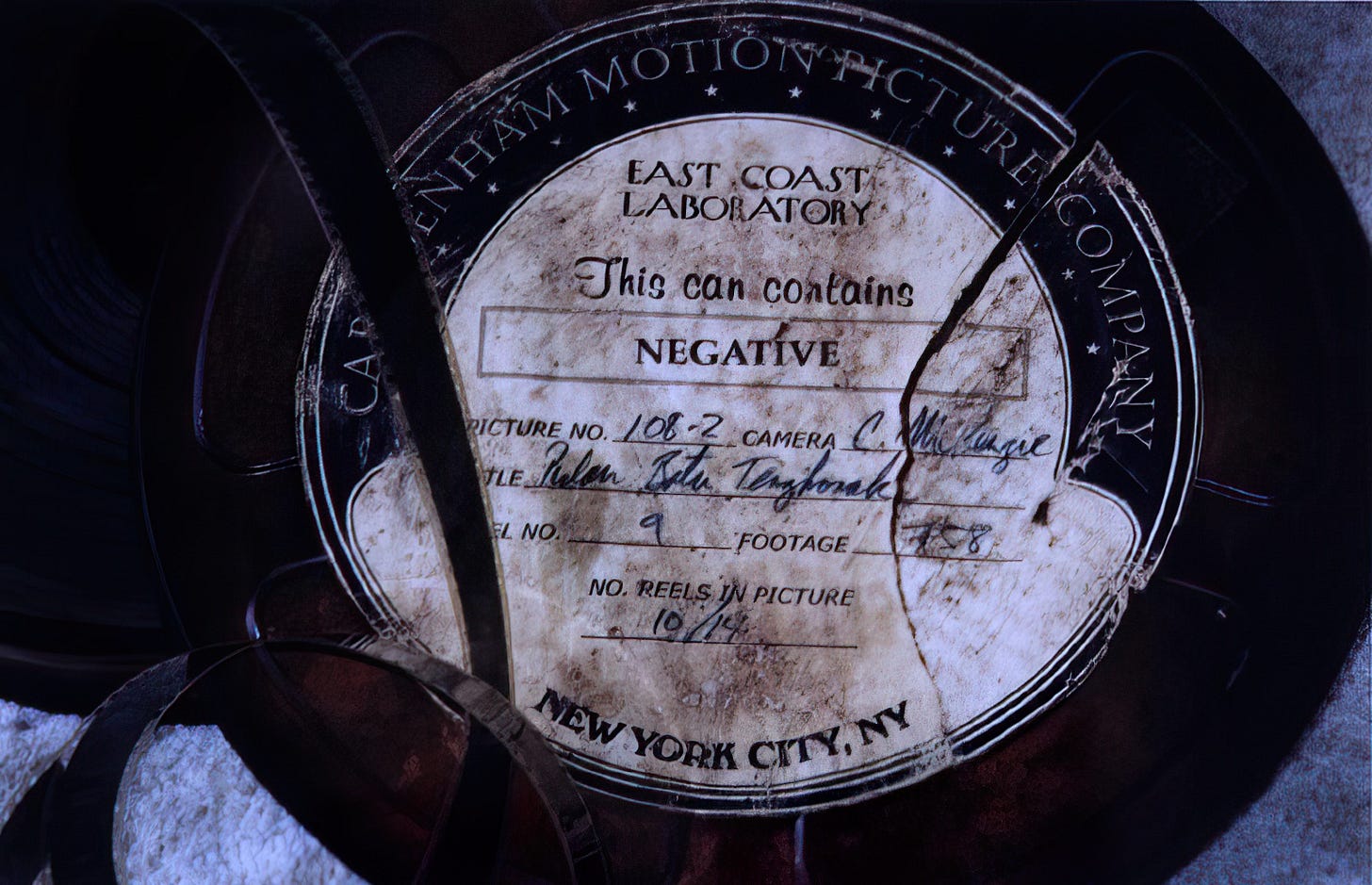

At his feet was a cheap canvas clutch he’d lugged all the way over from RKO, filled with what Tolliver assumed would be a new addition to some rich bastard’s film oddity collection. It’d been easy enough to game the RKO film library records and get out every single can marked “Carl Denham Motion Picture Company” as per the client’s wishes. The usual arrangements were in place: one additional inside player to deal with clerical issues in exchange for a slice of the pie, cash on delivery of goods, amount dependent upon quantity of film turned over. Easy money, and no one gets hurt. Just that much less fodder for the furnaces and garbage scows, eventual destinations for RKO’s excess nitrate stock.

This particular setup was not a whole lot different from his previous errands. It was the natural order of things; unnamed millionaire has a hankering for something no one else gets to see and pays handsomely for the privilege. “Screen tests” of starlets willing to do anything to make it were usually on the menu, and if the occasional unknown caught frolicking on film suddenly makes it big, some rich guy in Beverly Hills or a New York penthouse has the result for his eyes only. Tolliver felt certain that he, in his own way, played a role in making sure that an important line would not be crossed, and normal workaday folks would never see the naked indiscretions of America’s treasured celebrities.

He had his place in the overall ecosystem of Hollywood—like beetles on the jungle floor that eat the dung of larger animals, keeping things clean while enriching themselves.

Just like something from a Denham film, he thought to himself.

In this case he’d evidently hooked into a rich guy who liked oddities of nature. Seven hundred bucks per reel of film, he was told, as long as it was shot by Carl Denham. The “King Kong” stuff RKO had kept stored for years now, doing nothing but taking up space. It was cataloged and inventoried loosely, as if they wanted it to go missing. Tolliver’s inside person had too easy a job for a full thirty percent of the take, he thought. But that was the understanding, and there was no use getting dishonest at this stage of the game.

The sedan rolled up at last, twenty minutes late. “John” got out, alone as usual. He adjusted his fedora as he walked and came right to the point without pleasantries (also as per usual).

“How many?” he said by way of greeting.

“And a good evening to you as well,” Tolliver spat out sarcastically. He grabbed the clutch and unzipped it on the ground, beckoning the man down where they could see by the glow of a flashlight.

“Seven reels, nearly all full,” Tolliver said. “That’s $4900, which you should round up to five grand for making me wait in this weather.”

The dark suit didn’t acknowledge him, instead looking carefully at each film can label. “What’s this?” he said sharply.

“That’s what your guy wants. King Kong stuff. Nobody’s seen that,” Tolliver replied in rapid-fire fashion.

“No, this label says ‘RKO’ and ‘Cooper-Schoedsack.’ That’s not what he wants.” He flipped the can back to a crestfallen Tolliver and went to his pocket for cash. “Six cans, one’s a half-reel. Four thousand.”

“How about five hundred for the RKO can? It says ‘spiders’—that’s gotta be exciting!” The guy thinks I’m nothing but a schnorrer, Tolliver thought.

“I don’t know or care why my guy is after the Denham stuff, but that’s all he’s interested in. Take four and be happy.” He handed over a stack of bills as if the transaction were complete. Tolliver scowled and pocketed the money.

“You get more, you know the number,” dark suit said as he walked back to the sedan.

Tolliver nodded and started his long walk home. The rejected film can was now dead weight he could do without, so it went into the nearest garbage can.